Another character that our films hero Armand Roulin meets in Auvers-sur-Oise is The Old Man. As Armand talks to the people of Auvers who knew Van Gogh when he lived there, he meets The Old Man thatching a roof, who tells Armand what he remembers about the ‘painter fellow’ as the two share some cider.

We based this character in the film on Vincent’s paintings of Patience Escalier from 1888.

Vincent wrote about these portraits of his peasant model to his brother Theo, and his friend Emile Barnard. Whilst in our story Armand meets The Old Man in Auvers, this local peasant shepherd was actually one of the first people who agreed to pose for Vincent when he arrived in Arles.

“It’s a study in which colour plays a role that the black and white of a drawing couldn’t convey. The colour suggests the scorched air of harvest time at midday in the blistering heat, and without that it’s a different painting.”

Vincent van Gogh in a letter to Emile Bernard. Arles, August 1888.

For Loving Vincent’s live action filming, James Greene played The Old Man. Our Painting Animators used this reference footage along with Van Gogh’s paintings of Patience Escalier to then paint the frames of his scenes on canvas.

A final painting of The Old Man from Loving Vincent.

Louise Chevalier was Dr Paul Gachet’s housekeeper in Auvers-sur-oise. When Vincent van Gogh left the asylum in Saint Remy in May 1890, he went to live in Auvers, so Dr Gachet could keep an eye on him. In the film, our hero Armand Roulin comes across Louise on his journey to discover more about Van Gogh, and she shares her opinions and theories about the artist and his mysterious death with Armand.

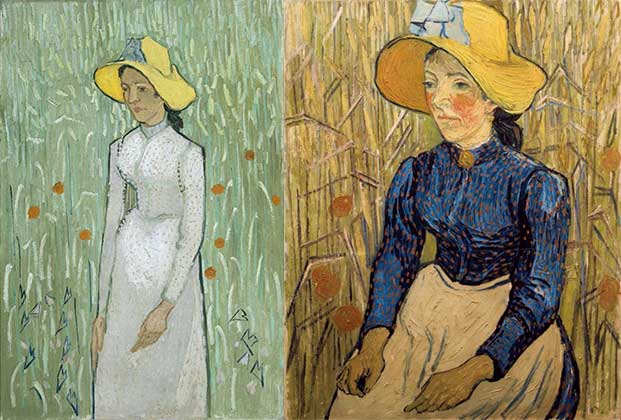

Vincent didn’t paint Louise, so we decided to use the two portraits he did of an unnamed woman in Auvers, ‘Girl in White’ and ‘Peasant Woman Against Background of Wheat’ for her character in the film.

“A figure of a peasant woman, big yellow hat with a knot of sky-blue ribbons, very red face. Coarse blue blouse with orange spots, background of ears of wheat.”

Van Gogh describes the second painting in a letter to his brother Theo in July 1890

Helen McCrory played Louise Chevalier in our live action shoot for our Painting Animator’s reference footage.

One of the characters that Armand Roulin meets in his investigation in Loving Vincent is The Boatman. Our inspiration for this character was Van Gogh’s Bank of the Oise at Auvers. We needed to adapt this to a portrait keyframe for our character, which fitted in with the style of Vincent’s original.

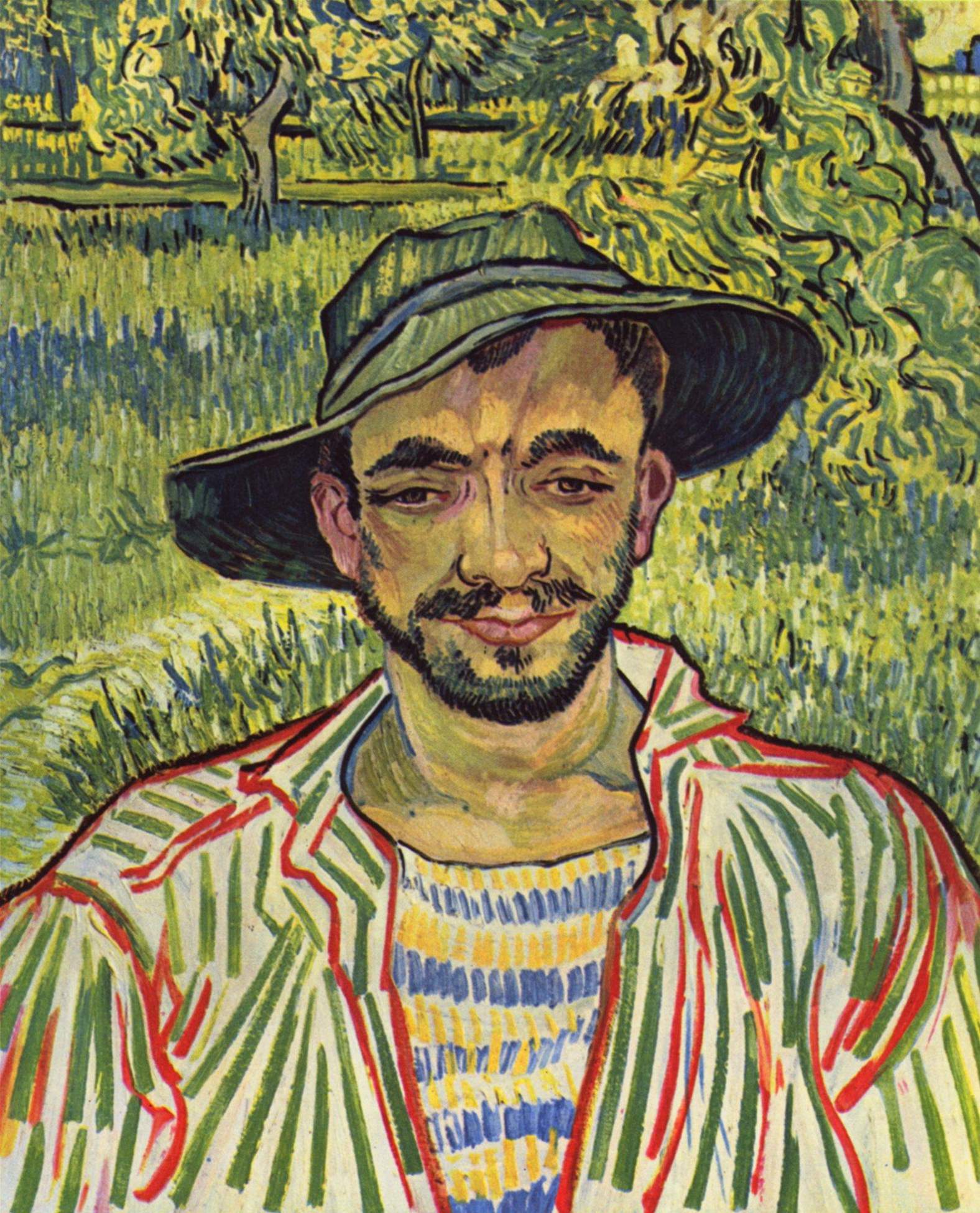

Painter Wiktor Jackowski created our keyframe for The Boatman. The Boatman is painted freely, fast and small within the composition of the original Vincent painting, so Wiktor and director Dorota Kobiela decided to use Van Gogh’s Portrait of a young peasant as the reference for painting the style of his face, shirt and hat.

We chose this painting because the face colouring and shape was similar to our actor Aidan Turner and in our script the boatman works outdoors, so this portrait fitted well in terms of personality as well.

For colour reference Wiktor used the Portrait of Armand Roulin, as for both Boatman scenes he would be sitting next to Armand, so they would need to feel congruous. He is darker than Armand, because he works outdoors in the sun, but we needed to feel that the characters fitted together. A sketch for the character keyframe was done with Armand in the frame so Wiktor could work out how the colours would work together.

An expanded keyframe test with Armand

The background reference for the colours and the style of brush strokes came from the Bank of the Oise at Auvers. As we were going in closer than the original, the brush strokes would be bigger, so we focused on the rhythm and the dynamic of applying the brush-strokes because this is what is so characteristic about Vincent’s original painting. Technically it was important to apply the brush-strokes quickly in the correct order, so that the paints would mix on the canvas. The shading choices were made to allow the character to stand out from the background, centering the viewers focus on him.

The final keyframe

Julien Tanguy, affectionately nick-named Père Tanguy, ran a paint supply shop in Paris, and Vincent van Gogh was one of his frequent customers and a loyal friend. Père Tanguy was a passionate supporter of the ’new painters’ including the impressionists, exhibiting them and often accepting payment for supplies in paintings. In Loving Vincent, Tanguy’s shop is Armand Roulin’s first stop on his journey to discover the truth about Van Gogh.

‘Do you know Tanguy? 14 rue Clauzel; an ugly-looking shop, and so small! Go in and you’ll see treasures out of the Arabian Nights… This Père Tanguy, what an astute spotter of masterpieces! How good he’s been at discovering today’s unknowns, tomorrow’s masters!… But let’s go in with no more ado… Look, here are some incomparable marvels by Cézanne! Look, here are some canvases by Vincent, extraordinarily fiery, intense, sunny’

Art critic Albert Aurier in Le Moderniste Illustré, April 1889

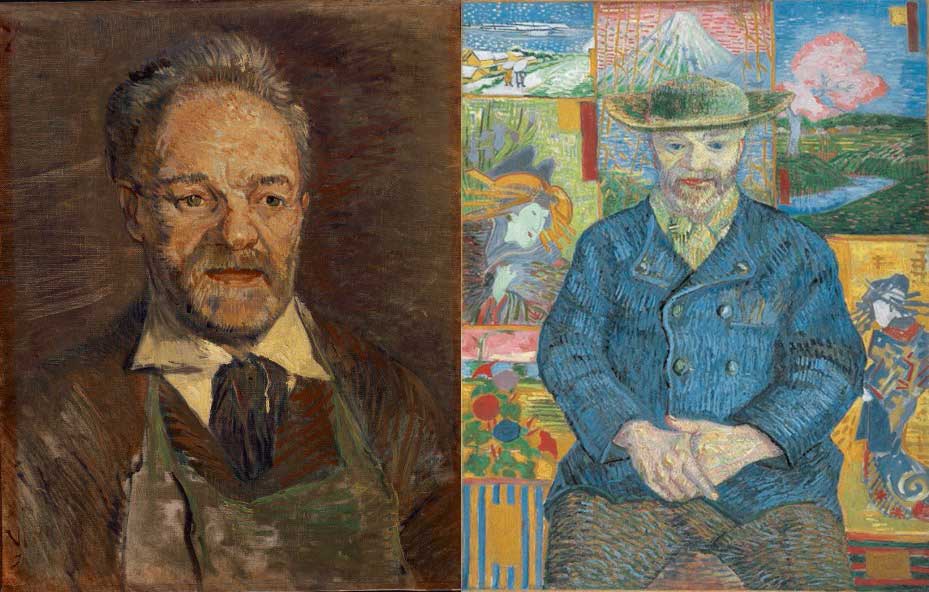

Vincent painted three portraits of Père Tanguy. The second painting took a revolutionary new approach from his previous work, heavily influenced by Japanese prints, which had a profound affect on Vincent’s attitude to framing and colour. This was one of the very first paintings that can be considered to be a transition from the experimentation of Vincent’s Paris paintings into a distinctive and unique style of his own.

We chose this second portrait for the basis of our Père Tanguy character. It shows his stoicism, his cordial confidence, calmness and the goodness of his character. These traits were evident underneath his not so delicate features, his small eyes without any trace of malice, always full of emotion. Tanguy kept this portrait of himself all his life, and after his death the sculptor Auguste Rodin purchased it.

Actor John Sessions played Père Tanguy in our live action filming.

Adeline Ravoux was the innkeeper’s daughter at the Ravoux Inn, where Vincent van Gogh resided during his time in Auvers-sur-Oise, and where he finally died on the 29th July 1890 from a gunshot wound. When he first arrived in Auvers, Vincent’s doctor Paul Gachet had recommended a boarding house that cost twice what Vincent was paying at Ravoux Inn, but he elected to take the cheapest room - the attic room, at the Ravoux.

A photograph of the Ravoux Inn at the time

Vincent created 68 paintings in his 70 days in Auvers, including three of Adeline Ravoux, despite her only posing once. Adeline was one of only four people ever interviewed about Vincent who knew him when he was alive, although her testimony was given 66 years after his death. We used the account given by the 79 year old Adeline as the basis for the character that we created, played by Eleanor Tomlinson.

Our footage alongside Van Gogh’s portrait and our final keyframe.

“This week I’ve done a portrait of a young girl of 16 or so, in blue against a blue background, the daughter of the people where I’m lodging.“

Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his brother Theo. Auvers, 24 June 1890.

In the story of our film, Armand Roulin travels to Auvers after Vincent’s death and he too elects to stay at the Ravoux inn, where he befriends Adeline as she recounts her memories of Vincent’s life and death.

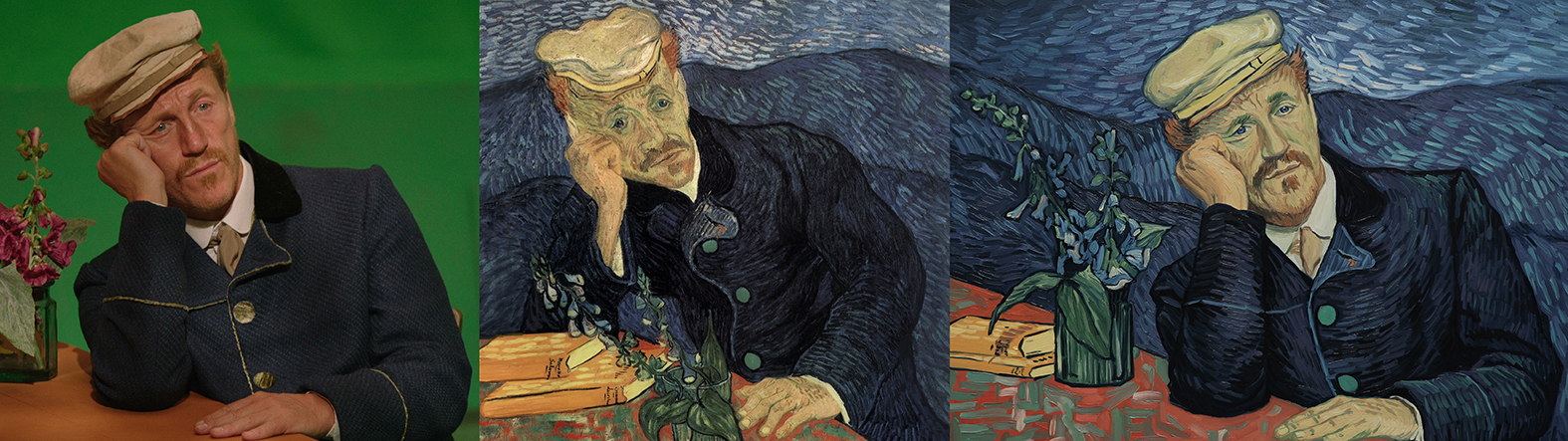

Dr Paul Gachet was passionately involved with the bohemian world of the impressionist artists of Paris. He was a physician to many painters including Cezanne, and became Van Gogh’s doctor in Auvers-sur-oise after Vincent left the Saint Remy asylum, following a recommendation from Camille Pissarro to Vincent’s brother Theo. Vincent lived in Auvers so he could be treated by Dr Gachet from May 1890 until his death in July that year. Actor Jerome Flynn starred as Dr Gachet in the reference material our painters used to create Loving Vincent.

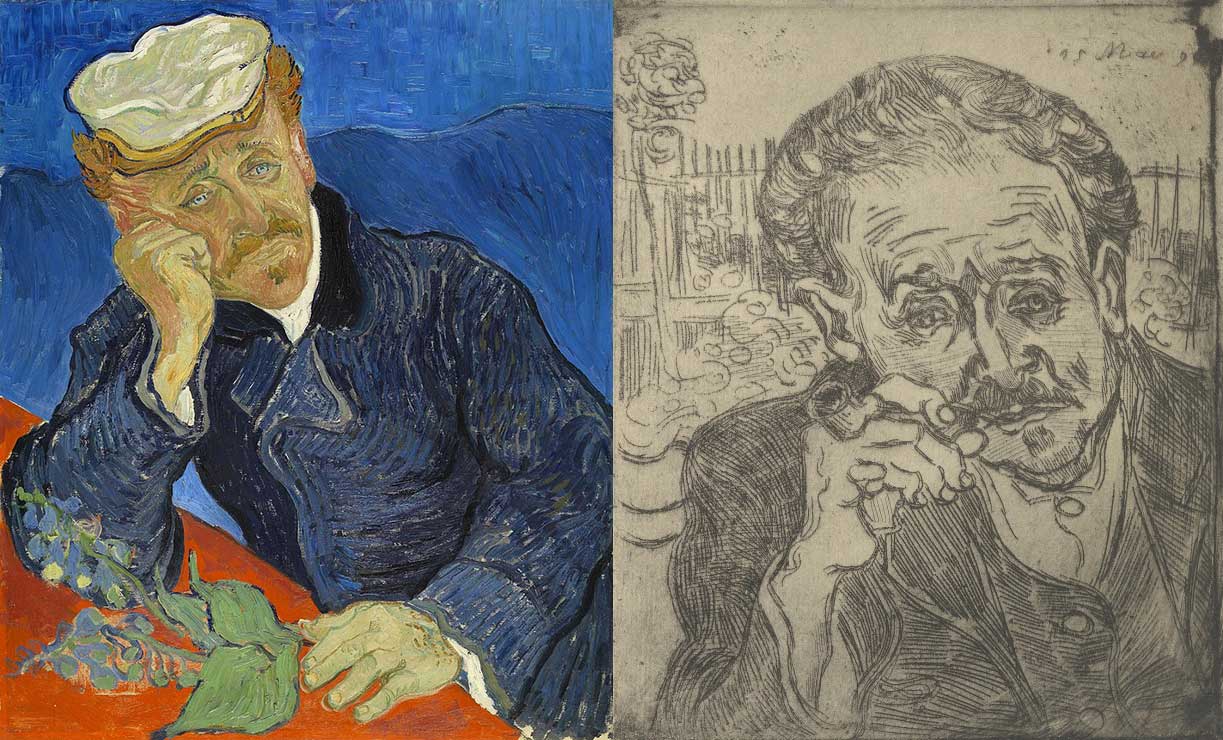

Jerome Flynn during filming, Vincent’s portrait of Dr Gachet and our keyframe combining the two.

Dr Gachet was an aspiring painter himself, and he and Vincent quickly became firm friends. Whilst Vincent was in Auvers, he painted fervently, creating a new canvas almost daily. He visited Dr Gachet regularly and painted his daughter Marguerite twice as well. Marguerite appears in Loving Vincent, played by Saoirse Ronan, and we also meet the Gachet’s housekeeper, Louise Chevalier, played by Helen McCrory.

“I’ve found in Dr Gachet a ready-made friend and something like a new brother would be – so much do we resemble each other physically, and morally too. He’s very nervous and very bizarre himself, and has rendered much friendship and many services to the artists of the new school, as much as was in his power. We were friends, so to speak, immediately, and I’ll go and spend one or two days a week at his house working in his garden, of which I’ve already painted two studies.”

Vincent in a letter to his sister Willemien, Auvers-sur-Oise, 5 June 1890

Vincent’s painting of Dr Gachet with his iconic melancholy expression broke auction records when it went on sale in 1990, selling for $82.5 million. This painting remains in a private collection, but Vincent also produced a copy which is on display at the Musee D’Orsay. Gachet also had his own etching press and Vincent produced his only ever etching, Portrait of Dr Gachet with Pipe, during this period.

Van Gogh’s second portrait and etching of Dr Gachet

After Vincent’s death, Dr Gachet claimed many of Vincent’s paintings as payment for the treatment he provided. Gachet spent the final years of his life imitating them, and aimed to write a biography of Vincent, although this never came to fruition.

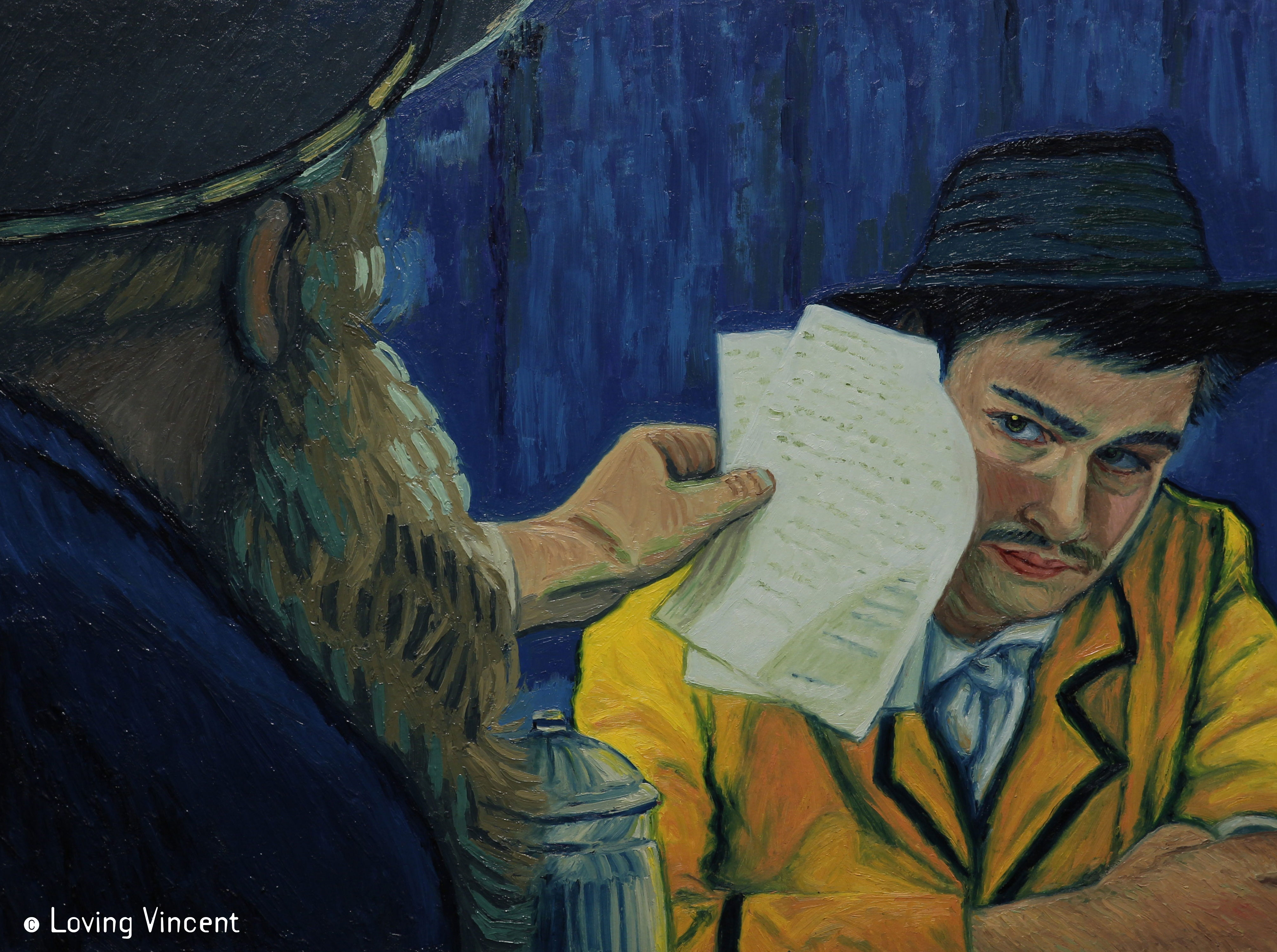

In Loving Vincent the young Armand Roulin travels to Auvers to meet the mercurial Doctor and find out what he made of Vincent’s sudden death. He also probes Gachet about the rumours of an argument between the two friends a few weeks beforehand….

.jpg)

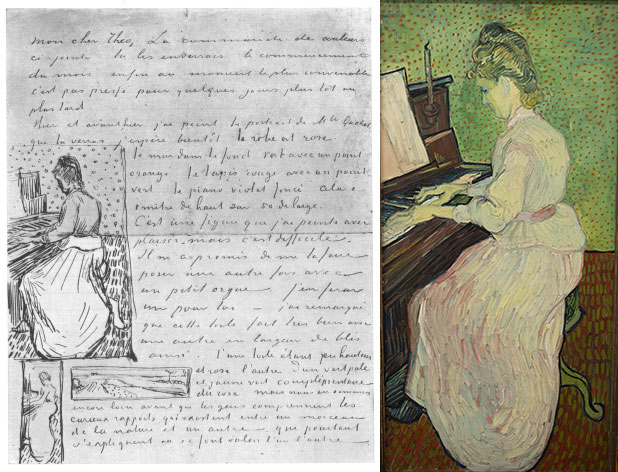

Marguerite Gachet was the daughter of Dr Paul Gachet, Vincent van Gogh’s doctor in Auvers-sur-Oise, where he spent the last few months of his life. Vincent regularly joined the Gachet family for meals and painted Marguerite twice, yet her face was always concealed.

“The wall in the background green with orange spots, the carpet red with green spots, the piano dark violet. It’s a figure I enjoyed painting – but it’s difficult.”

Vincent’s sketch and letter to his brother Theo from June 1980, alongside his final painting.

When we were making Loving Vincent, we had to extend the frame of Vincent’s original portrait to fit it on screen, adding to the surroundings in Vincent’s style..

Saoirse Ronan played Marguerite in the live-action filming that our painters used as reference footage. We talked to her about Van Gogh and the film process behind the scenes;

In Loving Vincent Armand Roulin travels to Auvers in his investigation into Vincent’s death, and meets many people there who have their own theories about the relationship between Vincent and Marguerite…

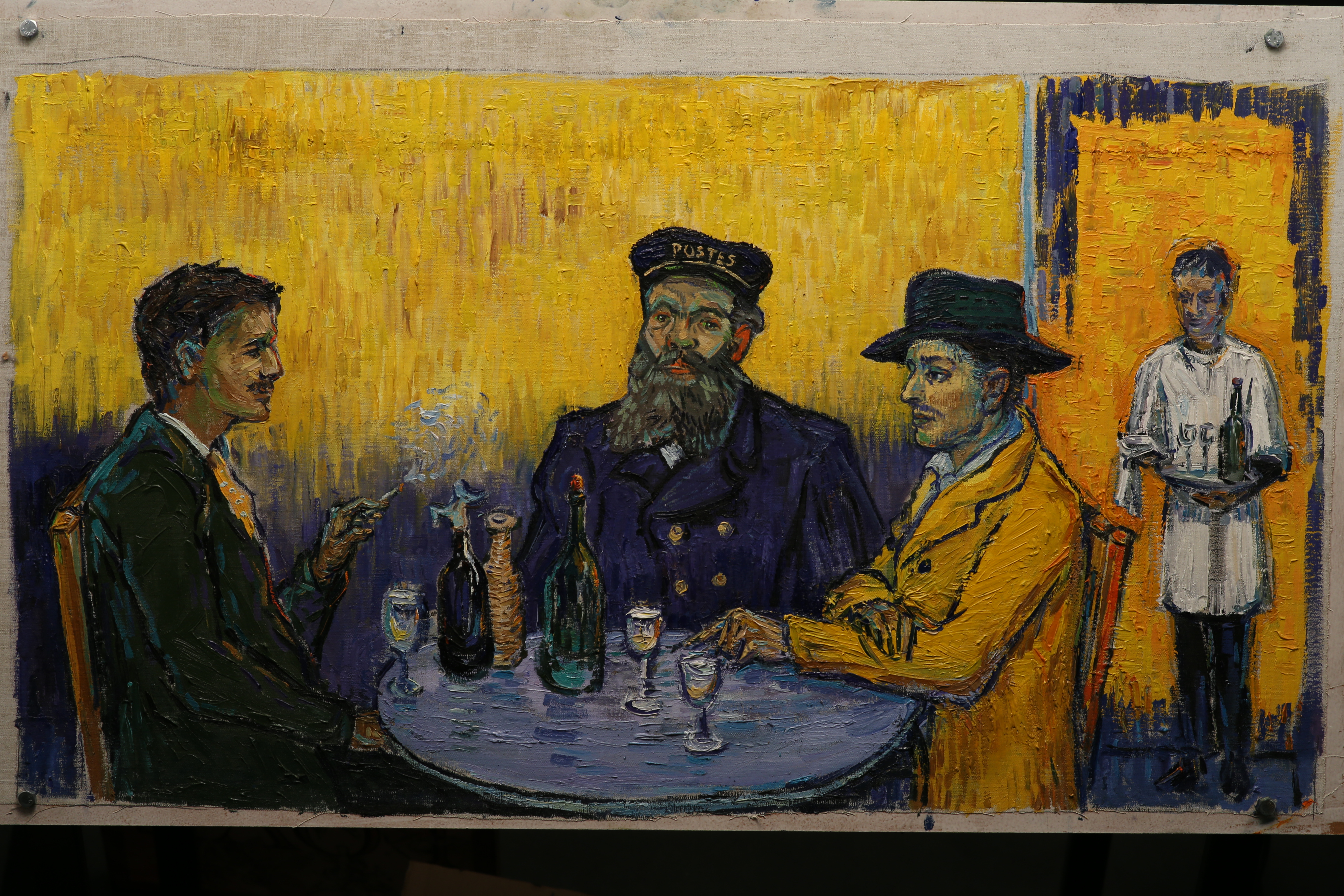

In Loving Vincent, Postman Joseph Roulin is a key character. He is the father of Armand Roulin, sending Armand on his quest to deliver a letter, and find out what really happened to Van Gogh.

Postman Roulin was Vincent van Gogh’s closest friend in Arles, unsurprising as Vincent was such a keen letter writer, and the two often drank together. Vincent painted 23 paintings of the various members of the Roulin family, including six paintings of Joseph Roulin, always in his Postman’s uniform and hat. He painted more portraits of Postman Roulin than of any other person, other than himself. Vincent described him in a letter to his brother Theo:

“Now I’m working with another model, a postman in a blue uniform with gold trimmings, a big, bearded face, very Socratic. A raging republican, like Père Tanguy. A more interesting man than many people.

Vincent van Gogh in a letter to Theo van Gogh, Arles, 31 July 1888.

‘Portrait of Postman Roulin’ and our final keyframe

We chose Van Gogh’s yellow Portrait of Postman Roulin for the basis of his character in the film because then we could set his argument with Armand in the famous Café Terrace at Night.

After the incident with the ear, Postman Roulin was there at Vincent’s ‘Yellow House’ the next day, and was one of the only Arles residents who stood by him afterwards. It was Roulin who cleared up his house, took him out of hospital, and was a pillar of strength for Vincent. Shortly after this, Roulin was assigned to work in Marseille, but they still exchanged many letters.

“Mr Vincent, please accept the sincere regards of all my family as well as those of him who declares himself your truly devoted friend.”

Postman Joseph Roulin in a letter to Vincent van Gogh, Marseille, 24 October 1889.

Chris O’Dowd as Postman Roulin, alongside Douglas Booth as Armand during the live action filming.

Loving Vincent follows the journey of Armand Roulin, son to Postman Joseph Roulin. In the film Armand’s father sends him to deliver a letter to Vincent’s brother Theo, after hearing that Vincent shot himself. Armand arrives in Paris only to find that Theo is dead too. He is drawn into the mystery of Vincent’s death, as he finds out more about Vincent’s amazing life and seeks out the truth about his death.

Armand Roulin lived just around the corner from the ‘Night Cafe’ and Vincent van Gogh’s ‘Yellow House’ in Arles, France. His father Joseph was one of Vincent van Gogh’s closest friends when he lived there, and Vincent painted portraits of all the Roulin family.

“I have done the portraits of a whole family, that of the postman whose head I did earlier – husband, wife, baby, the young boy and the 16-year-old son, all of them characters and very French, though they look Russian ”

Vincent van Gogh in a letter to Theo van Gogh. Arles, 1 December 1888.

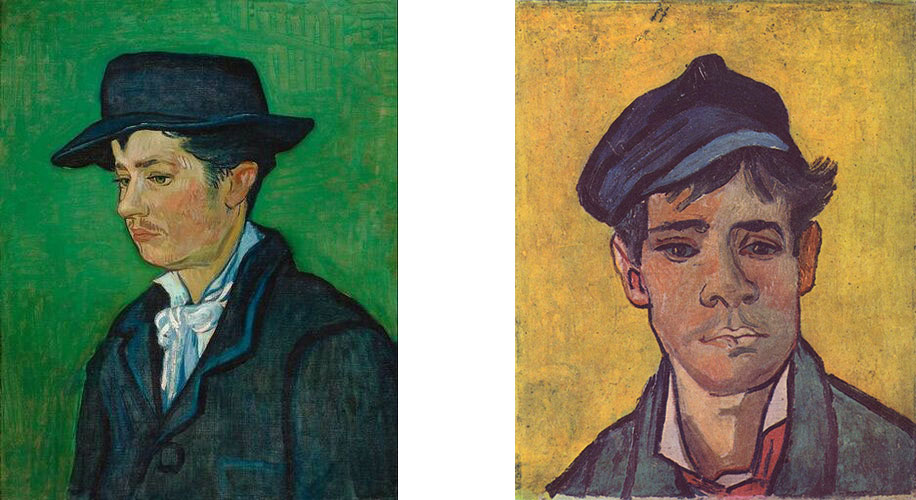

Vincent painted Armand three times, and his Portrait of Armand Roulin in a yellow jacket is the one from which we took a lead for Loving Vincent:

'Portrait of Armand Roulin’ and our final keyframe.

As a painting, the portrait of Armand Roulin is not one of Vincent’s most famous works. Armand Roulin didn’t have the significance in Vincent’s life that his father Joseph Roulin did. At various points in the Loving Vincent script writing journey other characters were the central protagonists of the story. However they all held strong views about Vincent, but we wanted a main character who started out rather indifferent to Vincent, and could be drawn into the mystery and magic of his world and the tragedy of his untimely death.

The portrait sits in the Museum Folkwang in Essen - here’s Loving Vincent co-Director Hugh Welchman visiting it:

Here are the two other paintings of Armand that Vincent made:

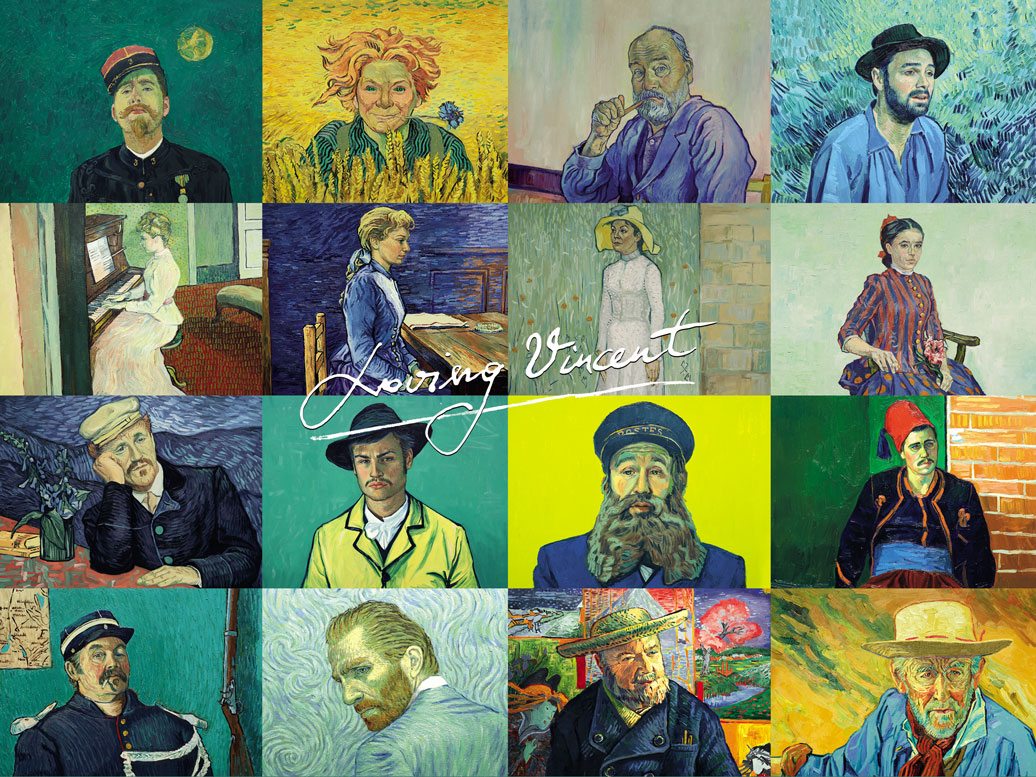

We wanted the films audience to be able to see the real people underneath the paintings, and the emotions on their face, so we cast actors who had a physical resemblance to the paintings and who could bring that painting to life. Douglas Booth was cast as Armand, and the live action filming of his scenes took place in 2015 in London.

This live action footage was then used by the 125 painters who worked on Loving Vincent as a reference for the 65,000 oil paintings that were created and animated to produce the final film. Vincent van Gogh experimented with a variety of painting styles and techniques, and our hero Armand often enters a scene painted in a different style to his own portrait in Loving Vincent. Our aim was that Armand should wherever possible, harmonise with the style of the painting he is invading.

The story of Loving Vincent begins one year after death of Vincent van Gogh, in the summer of 1891. Our hero Armand Roulin sets out to discover the truth about Van Gogh, and in doing so meets many people who knew Vincent when he was alive, and they share their memories of him with Armand.

Vincent was an avid letter writer and left behind over 800 letters which director-writer duo Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman drew from when writing the script for the film. They felt that the story of Vincent could only be properly emotionally told if it was intimately connected to his paintings, so we used the medium of paint, and 125 of Vincent’s paintings form the very fabric of the world in Loving Vincent.

“We cannot speak other than by our paintings”

Vincent van Gogh in a letter to his brother Theo, the week before his death in 1890

In our story, there are parts of Vincent’s life that he didn’t paint, so we came up with the idea of having flashbacks in the film. These are done in a black and white painted style, based on photographs from the era. This freed us up to show many dramatic situations from his life, without taking it upon ourselves to imagine entire series of paintings that Vincent never painted.

We found our Vincent, Polish theatre actor Robert Gulaczyk, in 2014. Here he is on set:

Vincent’s paintings changed painting and art forever, and after his death his fame grew until the point that he became the most famous artist in the world, whose work and writings have influenced the lives of millions of people. We hope that Loving Vincent will introduce more people to his work and life.

Loving Vincent first entered development in 2008, originally conceived as a short film by Dorota Kobiela. Since then the script has gone through several major drafts and changes in direction before settling on the final version, which tells the story from the point of view of Armand Roulin. Here are few words from writer-director duo Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman at various points in the journey.

Hugh Welchman and Dorota Kobiela

Dorota Kobiela - the early drafts

By far the hardest challenge was re-writing the script as an 80 minute film. I see myself as a director, not a writer. I couldn’t just write a biopic like Lust for Life, I could only have scenes that were set in or at least started or finished in Vincent paintings. I would often write scenes that I thought were beautiful and moved the story forward, and then realise they were too removed from the paintings.

Kirk Douglas as Van Gogh in Lust for Life

I wrote the first draft in Polish, based on my various short scripts, and using character monologues we had commissioned from a Polish novelist, Jacek Dehnal. I wrote the second draft in Polish as well, and it was so time consuming getting it translated, and getting notes in English, so, seeing as we were going to shoot the film in English, I decided I would write future drafts in English. So at this point I drafted in the help of Hugh and co-opted him as my co-writer. Over the next 2 and a half years we produced 5 full new drafts, and many minor revisions to those 5 drafts, and we had two complete changes of direction during this time.

I wrote many stories: stories taken from Vincent’s life; stories that started from particular paintings; stories exclusively from his Dutch period; stories when he was deep in the bohemia of Mountmartre in Paris. But the first concrete script that emerged was set during his last days. This resonated, and also I loved the paintings involved, and the fact they included paintings of people who he had regular contact with at the end: the mercurial Dr Gachet; his mysterious daughter, Marguerite Gachet, painted three times, yet her face always concealed; and the spirited daughter of the owner of the Inn where Vincent died, Adeline Ravoux.

Hugh Welchman and Dorota Kobiela working on a draft of the script in Amsterdam.

Hugh Welchman on developing the story

We had read around 40 different publications about Vincent: biographies, academic, essays and fictional works. Over 4 years we visited 19 museums in 6 countries to view around 400 Van Gogh paintings. We also watched the major feature film and documentary productions about his life and interviewed experts at the Van Gogh Museum.

The demands of writing a script on Vincent were tough. We took as our mantra his words in one of his last letters: “We cannot speak other than by our paintings”. So we showed only what we see in his paintings. With that restriction we had many paths to follow: Vincent’s struggle; the mystery of his death; the development of his art; or an alchemy of the aforementioned.

For us it was very clear that Vincent was not insane. The story shouldn’t be about his madness, it should be sheer bewildering shock at the journey he went on and what he accomplished in 8 short years. But we also had to deal with the widely held perception that he was some tortured mad suffering artist.

Vincent in the final film

New directions - Dorota

A major change of direction was the change from a mockumentary to a regular dramatic story. For the first draft we had the unseen film-maker as the driving force of the investigation into Vincent’s life through interviews with his paintings. We also made the stylistic choice to have two different visual styles in the film- the interviews would be in Vincent style, and the recollections of the people being interviewed would be in black and white.

One draft had Postman Roulin and his son narrating events to a third party, the painter Edvard Munch. They had looked into Vincent’s death, and now they were recounting this investigation to a painter who had come south in Vincent’s footsteps.

An early test painting with the Roulins and Edvard Munch.

We felt this was still too removed and we needed to identify more closely with the emotional journey of the main characters. So then we shifted to setting the investigation in the present, and made Armand Roulin the hero, interviewing people in Auvers, Paris and Arles.

Loving Vincent began development in 2008, and involved several years of testing and training before painting on the shots used in the final film began.

From various tests with computer animation we concluded that it was very important to actually, like Vincent van Gogh, paint with oils on canvas. Each frame of the film is an oil painting, based on or inspired by his paintings. We wanted real people to bring his portrait to life; actors rather than animations. By shooting live action with actors we created material in days that would normally take months in animation.

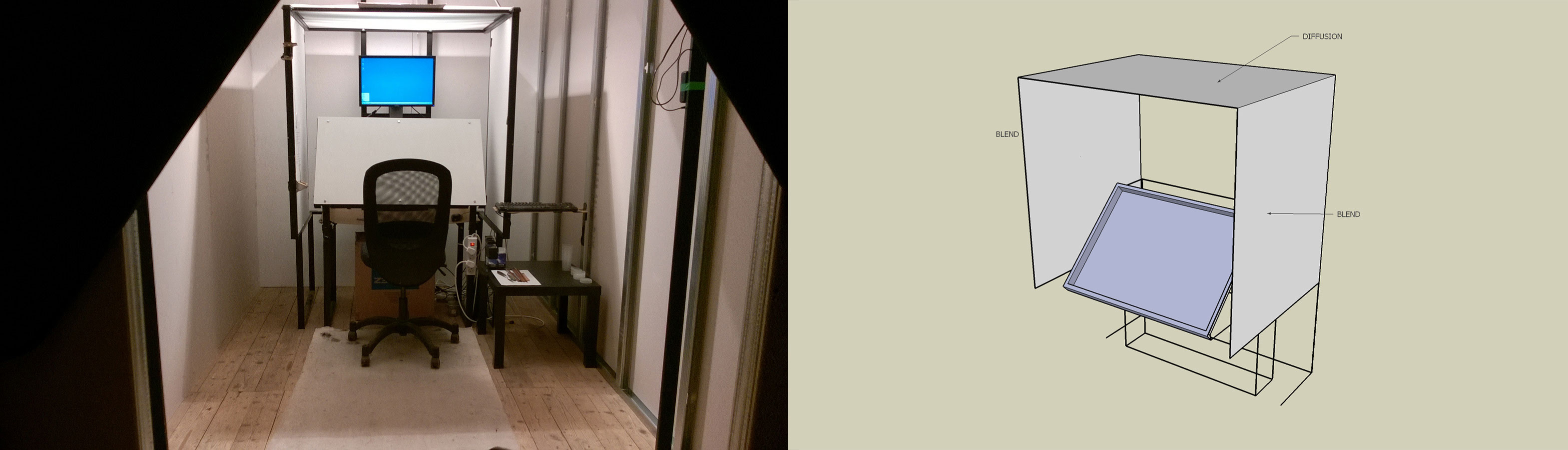

In 2012 Dorota Kobiela directed the concept trailer for the film and our first painters came on board. At the same time we also worked on a prototype for PAWS (Painting Animation Work Station), a workstation designed to make the painting animation process as efficient as possible.

In 2013 we shot test live action test footage in Poland in a freezing barn at -20c with members of the crew standing in as characters. We edited this together and used it as reference footage for the next stage of painting tests.

Hugh Welchman stood in as Vincent for our early test footage.

We researched and tested 9 different brands of oil paints from 6 manufacturers. We took into consideration quality of the paint, viscosity, how the colours came across, range of colours, and price. The colour that mattered most to us was yellow. We needed a brand that had a good range of yellows, and for the yellow to be very saturated.The tests consisted of applying paint to canvas boards and photographing them under different lighting conditions. Royal Talens Van Gogh was the obvious choice because it had the greatest range of colours, and additionally it was the cheapest of the 3 paints that passed our tests.

After we had fine tuned the painting process, we found and trained 40 more painters, whose training was partly funded by a Kickstarter campaign. In 2014 we were then able to start the design painting process, with 20 painters re-imagining the paintings of Vincent van Gogh for the big screen. The Painting Design team spent one-year re-imagining Vincent’s painting into the medium of film. There are 94 Vincent paintings that feature in a form very close to the original, and there are a further 31 paintings that are either featured substantially or partially.

Painters training in our Gdansk studio

Vincent’s paintings come in different shapes and sizes, so the design painters had to work out how to best show these paintings within the frame set by the cinema screen. This required breaking outside the frames of Vincent’s paintings, while still retaining the feel and inspiration of Vincent’s originals.

Expanding Van Gogh’s Le Moulin de la Galette

We also had to work out how to deal with ‘invasions’, where a character painted in one style, comes into another Vincent painting with a different style. The Character Design Painters specialized in re-imagining our actors as their famous portraits, so that they would retain their own features and at the same time recognizably take on the look and feeling of their character in painting form. There were 377 paintings painted during the Design Painting process.

To create Loving Vincent, we had to hand paint 65,000 frames of oil paintings. To make this process as efficient as possible, we spent 2 years during the development of the project working on our Painting Animation Work Stations (PAWS). Each of our Painting Animators, across 97 workstations in 3 studios in 2 countries, painted inside a PAWS.

When we originally had the idea for the film, the problem we faced was how we were going to be able to make it in a reasonable time frame. Our first simple painter setup was very home made: an easel; a camera; a tripod; ikea shelving unit; lamps; projector; computer; and a memory stick. Often we were losing time because the painter was knocking one of the main elements, and everything would have to be put back into alignment. Also people were walking around with memory sticks, and we had to go to the workstation to review the frames. This is fine when we had a handful of painting animators in one location, but wasn’t going to work when we had 97 across 3 locations.

So we started thinking about a workstation for our painters which would allow them to focus just on the painting, and allow us to view what they were doing without interrupting their flow. The new PAWS aimed to minimize time wasted on unnecessary actions, like turning the lamps on and off.

PAWS during our painter training period

Painter training lasted six weeks, and we used these PAWS units above. For the final film however, we needed to maintain constant light conditions, a crucial consideration for any animated film. We knew that the PAWS would need some sort of curtains, but they were too flammable to use as walls so we built plaster walled booths for the final PAWS design.

This provided a stable environment where everything is rigidly set in proportion - the canvas to the camera, the canvas to the projector, and the PAWS had its own native light source. This minimised the amount of things that could go wrong for our Painting Animators during a shot, and allowed them to focus as much attention as possible on painting and animating without being concerned about lighting and technology.

This new PAWS system, alongside the painters growing experience from training, enabled the average painting time to come down to 40 minutes per frame. The main light source came from a lamp placed right above the canvas, oriented downwards. We placed a diffusion filter on the upper part of the PAWS, to ensure the light was as even as possible and we used white blends on both sides of the canvas because the top lamp didn’t give enough light on the sides of the painted frames. As the lower part of the canvas was darker, we also added a second lamp, directed upwards toward the ceiling to reflect light.

Our Painting Animators used the reference footage which could either be projected onto the canvas area, or be viewed on an HD monitor above the canvas. Once each frame of painting was finished two photographs were taken with a Canon digital stills camera at 6k resolution. 24 of these high-resolution photographs of 12 frames of painting make up each second of the film.

Each shot (which varied in length) was painted on a separate canvas. The first frame was a full painting, then each subsequent frame was re-painted, matching the brushstrokes, colour and impasto of their previous frame, for all parts of the shot that are moving. At the end of each shot we are left with a painting of the last frame, which you can find examples of here.